nominate Lesser Black-backed Gull (L. f. fuscus)

nominate Lesser Black-backed Gull (L. f. fuscus)

(last update:

Amir Ben Dov (Israel)

Hannu Koskinen (Finland)

Mars Muusse (the Netherlands)

fuscus 1cy July

fuscus 1cy Aug

fuscus 1cy Sept

fuscus 1cy Oct

fuscus 1cy Nov

fuscus 1cy Dec

fuscus 2cy Jan

fuscus 2cy Feb

fuscus 2cy March

fuscus 2cy April

fuscus 2cy May

fuscus 2cy June

fuscus 2cy July

fuscus 2cy Aug

fuscus 2cy Sept

fuscus 2cy Oct

fuscus 2cy Nov

fuscus 2cy Dec

fuscus 3cy Jan

fuscus 3cy Feb

fuscus 3cy March

fuscus 3cy April

fuscus 3cy May

fuscus 3cy June

fuscus 3cy July

fuscus 3cy August

fuscus 3cy Sept

fuscus 3cy October

fuscus 3cy Nov

fuscus 3cy Dec

fuscus 4cy Jan

fuscus 4cy Feb

fuscus 4cy March

fuscus 4cy April

fuscus 4cy May

fuscus 4cy June

fuscus 4cy July

fuscus 4cy Aug

fuscus 4cy Sept

fuscus 4cy Oct

fuscus 4cy Nov

fuscus 4cy Dec

fuscus ad Jan

fuscus ad Feb

fuscus ad March

fuscus ad April

fuscus ad May

fuscus ad June

fuscus ad July

fuscus ad Aug

fuscus unringed Aug

fuscus ad Sept

fuscus ad Oct

fuscus ad Nov

fuscus ad Dec

Factors effecting the breeding success of two ecologically similar

gulls the Lesser black-backed gulls, Larus f. fuscus

and Herring Gull, Larus argentatus, at Stora Karlsö.

- Examensarbete 2006:1 - Degree project thesis Stockholm University -

Abstract

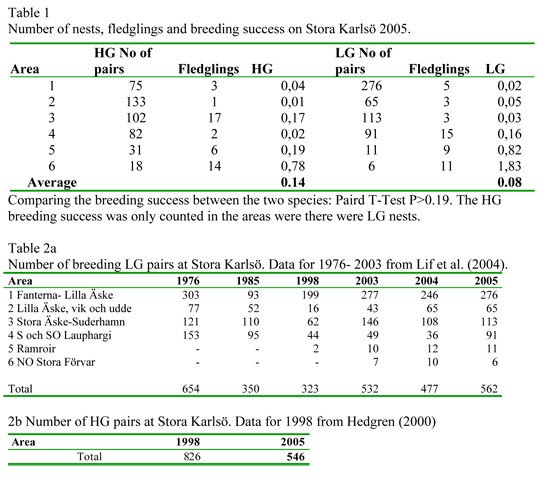

During the last three years the breeding success of the nominate lesser black-backed gull, Larus f. fuscus, at Stora Karlsö (near Gotland) has been monitored. Results indicate that the breeding success is too low to sustain the colonies (0.08 chicks/pair). This year Herring Gulls, Larus argentatus, were also studied and their breeding success was also surprisingly low (0.14 chicks/pair). The expected breeding success to maintain a sustainable population is 0.45 chicks/pair. For both species 83% of the chicks in the census disappeared without a known cause. The most likely reason for chick disappearance was predation.

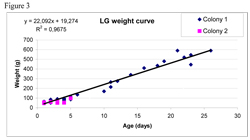

Predation by Larus argentatus explained the most of the chick disappearances for both species but didn’t alone explain the reproductive failure and the large number of chicks found dead. Starvation did not appear to be a significant factor as a majority of the chicks exhibited good growth rates. Only those chicks that were found dead did not exhibit good growth.

Factors influencing the breeding success negatively are cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo) colonies that compete for same nesting space with the Herring Gulls. Our presence in the hides from where we performed observations had a disturbing effect especially when we approached or left the colony. The presence and predation of Greater Black-backed Gulls (Larus marinus) was a stressful factor for both gull species. Factors affecting the breeding success positively were experienced parents (i.e. parents that arrived early and chose nest sites in vegetated areas with few neighbouring birds).

Discussion

There was no significant difference in breeding success between the two species studied. HG appeared to have a significant influence on the survival of LG through predation. There was no evidence of nesting site competition between the two species, due to different preference in choice of habitat in the areas. However some of the different surrounding factors between the areas had a negative effect on breeding success. It seems that the hides that where put up for observations of the colonies, in addition with cormorant colonies and density of nests within the species are interfering factors. Starvation did not seem to be an issue as the chicks’ growth rate was good. However all the chicks that were found dead were classified as being of poor condition, which may indicate that a disease or toxin had affected these chicks. Poor parental care (i.e. adults eating their own eggs or neglecting to feed their chicks, Hario 1990) may also have had a negative impact on the breeding success.

There was no significant difference in breeding success between the two species studied. HG appeared to have a significant influence on the survival of LG through predation. There was no evidence of nesting site competition between the two species, due to different preference in choice of habitat in the areas. However some of the different surrounding factors between the areas had a negative effect on breeding success. It seems that the hides that where put up for observations of the colonies, in addition with cormorant colonies and density of nests within the species are interfering factors. Starvation did not seem to be an issue as the chicks’ growth rate was good. However all the chicks that were found dead were classified as being of poor condition, which may indicate that a disease or toxin had affected these chicks. Poor parental care (i.e. adults eating their own eggs or neglecting to feed their chicks, Hario 1990) may also have had a negative impact on the breeding success.

We studied two colonies, one that contained only LG and one where HG and LG were mixed. The two species did not have their nests close to each other and did not appear disturbed by the neighbouring species. In Gjaushäll where the two species breed together some of the LG eggs didn’t hatch until eighteen days later than the HG eggs. According to Kim (2003 and 2005) the HG and LG that arrived late to a location are most likely first year breeders and subsequently their chicks hatch later. Hatching late could deprive the chicks the protection of the colony from predators as the adults loose interest in protecting the colony as soon as their chicks become older (pers.obs.). The LG in Gjaushäll could be young breeders as they chose such an unsuitable site, by the seashore on the rocks unlike the colony 1 in Langdal where the vegetation consisted of juniper and tall grass. The breeding success in colony 2 was zero.

Out estimates of the number of fledglings can have been biased in three ways. During the assessment, some birds flew away and might have been counted twice. It is also possible that fledglings move from their colony into other areas due to the territories not being guarded when the chicks are older. In addition, juvenile HGs and LG are very similar and therefore may have been mis-identified. In this study the number of breeding LG pairs was 562 with a breeding success of 0,08 fledglings per pair. This could be seen as a small increase from the previous year, 477 and 0,02 fledglings. I did not take into account the late breeders as was done in Lif et al. (2005) where the numbers were estimated to 600 pairs at Stora Karlsö. It appears that the size of LG population on Stora Karlsö has been the same over the last three years. Even thou we spent substantially more time observing LG this year (238h of which 146h in Gjaushäll) compared to previous year (52h) we were unable to determine the fate of all chicks. Most of the chicks of both species disappeared. The possible causes for the chicks’ disappearances were: predation or dying of unknown cause, a few of the dead chicks that we found were quite hidden in the scrubs and it’s likely that there were more chicks that we didn’t find.

Predation

Herring gull was the main predator on LG chicks, with a successful attack rate of 60%. A smaller number of attacks on LG were done by conspecifics, but these attacks could also have been territorial markings and not an attempt to eat the chicks. Very few attacks by greater black-backed gulls were observed, which could be due to our presence in the hides that appeared to stress them. It is not impossible that the Greater black-backed gulls eat a substantial amount of the LG chicks. Lif observed four LG chicks being eaten by Greater black-backed gulls in 2004. From my own observations and as shown by Hario (1996), it appears that only healthy chicks were predated on. In our study 68% of the observed healthy chicks of the LG and 47% of the HG chicks were predated. There were no predation attempts on the chicks that were observed dying. If fewer chicks are healthy the few that are healthy will probably be eaten. This would mean that the viability of the colony would be reduced and the breeding success would decrease. The high percentage of predation by HG could also be the result of an observer being present and making the LG parent nervous and leaving the nest unattended.

Herring gull was the main predator on LG chicks, with a successful attack rate of 60%. A smaller number of attacks on LG were done by conspecifics, but these attacks could also have been territorial markings and not an attempt to eat the chicks. Very few attacks by greater black-backed gulls were observed, which could be due to our presence in the hides that appeared to stress them. It is not impossible that the Greater black-backed gulls eat a substantial amount of the LG chicks. Lif observed four LG chicks being eaten by Greater black-backed gulls in 2004. From my own observations and as shown by Hario (1996), it appears that only healthy chicks were predated on. In our study 68% of the observed healthy chicks of the LG and 47% of the HG chicks were predated. There were no predation attempts on the chicks that were observed dying. If fewer chicks are healthy the few that are healthy will probably be eaten. This would mean that the viability of the colony would be reduced and the breeding success would decrease. The high percentage of predation by HG could also be the result of an observer being present and making the LG parent nervous and leaving the nest unattended.

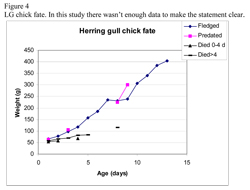

A way to get an indication to the fate of the disappearing chicks is to look at the weight curves. Hario (1996) illustrated a weight curve of chicks with five different fates: fledged, predated, died 0-4 days, died >4 days and disappeared. The data in our study of LG was not enough to do a similar graph although for HG we had more data (figure 4). Hario (1996) showed that chicks that died from other causes than predation whatever the age, didn’t gain weight. Chicks that fledged or got preyed on followed a healthy curve. However Hario (1996) put all the disappeared chicks in one category together, which may have biased the results.

Instead of putting them together one could take the weight curve of each individual chick and place it in the graph with the compatible category (i.e. the weight curve that matches the unknown-fate chick weight curve) and be able to predict the fate of each individual. If the unknown-fate chick has a healthy weight curve then one can possibly rule out that it has died of disease.

L. f. fuscus 1cy CYCE September 06 2003, Tampere, Finland (61.33N 24.59E). Picture Visa Rauste. Complete juvenile plumage.

L. f. fuscus 1cy CYCE September 06 2003, Tampere, Finland (61.33N 24.59E). Picture Visa Rauste. Complete juvenile plumage. L. f. fuscus C1C4 1cy, September 11 2013, Kaunas, Luthuania. Picture: Boris Belchev.

L. f. fuscus C1C4 1cy, September 11 2013, Kaunas, Luthuania. Picture: Boris Belchev. L. f. fuscus C8A9 1cy, September 11 2013, Kaunas, Luthuania. Picture: Boris Belchev.

L. f. fuscus C8A9 1cy, September 11 2013, Kaunas, Luthuania. Picture: Boris Belchev. L. f. fuscus 1cy C51X September 28 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Replacing scapulars.

L. f. fuscus 1cy C51X September 28 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Replacing scapulars. L. f. fuscus 1cy HT-253999 September 24 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Complete juvenile plumage.

L. f. fuscus 1cy HT-253999 September 24 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Complete juvenile plumage. L. f. fuscus 1cy HT-192171 September 17 2012, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Single scaps replaced.

L. f. fuscus 1cy HT-192171 September 17 2012, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Single scaps replaced. L. f. fuscus J102K 1cy, September 26 2014, Katwijk aan Zee, the Netherlands. Picture: Ed Schouten.

L. f. fuscus J102K 1cy, September 26 2014, Katwijk aan Zee, the Netherlands. Picture: Ed Schouten. L. f. fuscus 1cy September 17 2010, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Complete juvenile plumage.

L. f. fuscus 1cy September 17 2010, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Complete juvenile plumage. L. f. fuscus 1cy September 17 2010, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Complete juvenile plumage.

L. f. fuscus 1cy September 17 2010, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Complete juvenile plumage. L. f. fuscus 1cy September 24 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Complete juvenile plumage.

L. f. fuscus 1cy September 24 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Complete juvenile plumage. L. f. fuscus 1cy September 23 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Complete juvenile plumage.

L. f. fuscus 1cy September 23 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Complete juvenile plumage. L. f. fuscus 1cy, September 29 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov.

L. f. fuscus 1cy, September 29 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. L. f. fuscus 1cy, September 29 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov.

L. f. fuscus 1cy, September 29 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov.